R. Quentin Grafton, Asit K. Biswas, Hilmer Bosch, Safa Fanaian, Joyeeta Gupta, Aromar Revi, Neha Sami and Cecilia Tortajada

GLOBAL WATER FORUM | March 14, 2023

A just-published, multi-authored article in Nature Water (Grafton et al, 2023) highlights what progress has been made in responding to the world’s water crisis since the first UN Water Conference in 1977. The authors who are based in Australia, India, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom conclude that while much has been achieved, especially in terms of Water, Sanitation and Health (WASH), water remains too little, too much or too dirty for too many. At the UN 2023 Water Conference, New York, 22-24 March 2023 they argue for transformational change to expand WASH investments beyond ‘pipes and toilets’, to invest much more in green infrastructure, and to radically reform how water is governed to deliver ‘Water for All’.

Harold Wilson, a former British Prime Minister, once remarked that ‘a week is a long time in politics’. If this is true for politics, then it has been an eternity since the first UN Water Conference. It took place in 1977 over 11 days in Mar del Plata, Argentina while the second UN water Conference is scheduled 46 years later, over three days in March 2023, in New York City.

To appreciate how long it has been since the first UN Water Conference, in March 1977 the world had almost 4 billion fewer people, Jimmy Carter was the US President, Indira Gandhi was Prime Minister of India and ABBA had a global musical bestseller with ‘Dancing Queen’. The Vietnam War had ended less than two years previously and just 6 months earlier Chairman Mao Zedong (the founder of the People’s Republic of China) had died. The world was a very different place.

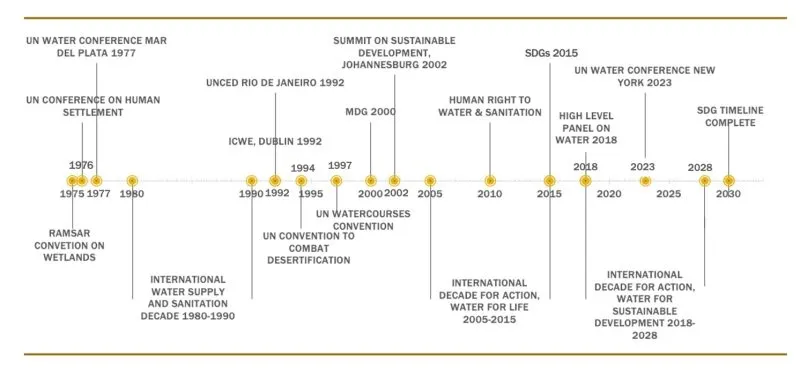

If the world has changed so much since 1977, what progress have we made in terms of resolving the world water crisis? (See figure 1 for key UN water related events since 1977.) A key goal of the first UN Water Conference was to avoid a water crisis of global dimensions by 2000 and to ensure an adequate supply of good quality water to meet socio-economic needs. Unfortunately, since 1977 globally freshwater has become scarcer per person, more polluted and more in demand, resulting in increased competition and conflict.

The good news is that progress has been made, especially in terms of access to Water, Sanitation and Health (WASH). Today, 70% of the world’s population has access to safely managed water; a doubling in the proportion of the global population with “safe” water since 1977. Nevertheless, less than 30% of Africans have access to safely managed drinking water services compared to more than 90% of North Americans and Europeans. And there is limited trust in the quality of water supplied via taps in many low-income countries.

Some 60% of people today have access to safely managed sanitation services, up from about 25% from the time of the first UN Water Conference. Yet 1.7 billion people still lack basic sanitation services, and at least half a billion people are forced to defecate in the open. Socio-economic disadvantage, exacerbated by COVID-19, has increased the number of people and communities that face water risks noting that women and children bear a disproportionately higher burden.

Data on what is happening in the Water World is also much improved since 1997 but key gaps remain. For example, metrics on access to sanitation and discharge of safely treated domestic and industrial wastewater are not reported by most countries. What is not measured is, typically not managed. But even what is measured may not always reflect reality; access to ‘clean’ water for all does not necessarily mean accessible water is safe for drinking, cooking, or washing.

Transboundary water issues also remain strained despite numerous bilateral and multilateral treaties intended to share surface waters more equitably.

One of the most important water-related shifts in science and perception since 1977, is the climate emergency. At a multilateral level it was first articulated as a global challenge in 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), known as the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro but has now taken a pivotal position in global environmental negotiations and is the zeitgeist of the 21st century. Too much and too little water, are the most significant climate change impacts. Yet given the overwhelming narrative and centrality of temperature overshoot, the critical connections between irreversible changes in the global water cycle and climate actions, for both climate mitigation and adaptation, remain weak in the policy space. This is despite robust and scientific evidence that water is an organising principle for climate resilient development.

The score card is, sadly, poor in terms of how we treat water and nature. More than a third of the world’s wetlands were lost between 1970 and 2015, primarily due to land-use change and inappropriate or ineffective water regulation (drainage, over abstraction, salinisation, and river regulation). Global deforestation has continued and has resulted in declining water quality, increased flooding risks, and reduced and changing precipitation, among other consequences. The world freshwater withdrawals have almost doubled since the first UN Water Conference and, globally, exceed the sustainable global freshwater limit.

Looking to the future, what are the neglected priorities for UN 2023 Water Conference and beyond? First, ensuring access to safely managed water and sanitation for all is vital. But this must go beyond grey or hard infrastructure such as ‘pipes and toilets’ to include the informal water sector and deliver safe water to where people cannot access piped water. A WASH ‘rethink’ should also encompass the conservation of green infrastructure, especially in Africa. Green infrastructure is especially important to at-risk communities because it provides (for free) many valuable ecosystems services such as freshwater provision, sediment regulation, and flood mitigation. ‘Nature-based solutions’ are estimated to be cumulatively worth USD 3 trillion by 2050 in terms of avoided replacement costs for grey infrastructure. Yet it attracts only a fraction of the efforts and investments provided to grey infrastructure.

Second, the world must change how water is managed. Global challenges that need to be overcome include: too many institutions managing water without coordination, or even communication; path dependency in terms of how water property rights have been allocated; inadequate and inaccessible data and information; and conflicts between water user groups. Regulatory capture when state actors are ‘captured’ by vested interests, that occurs in both the Global North and South, must also change. The response to governance failures must be bespoke, but reforms include transparency about decisions processes, and who is involved and, wherever possible, independent regulatory oversight.

Third, we must go beyond the focus on market values to systematically include non-market values, such as social, cultural, and environmental values, frequently ignored in decision-making. A focus solely, or principally, on market values means that too much water is allocated for purposes that generate the highest market values (eg, cotton production), and too little water is allocated for non-market needs (eg, sustaining cultural ecosystem services). Both market and non-market values are needed to evaluate trade-offs and to reallocate water where it provides the highest societal benefits.

Getting the right mix of bespoke and inclusive approaches to water is vital if the world is to ensure ‘water for all’ and to leave no person, no place, and no ecosystem behind. It includes regulations, reporting, compliance, monitoring and enforcement, limits on water withdrawals, incentives for water users to conserve water where it is scarce, and policies that recognise: “The human right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity. It is a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights”. The world cannot afford to wait another 46 years to fix the water crisis. We need transformational change bespoke to local bio-physical and socio-economic contexts but that also delivers globally, ‘Water for All’.

Reference

Quentin Grafton R, AK Biswas, H Bosch, S Fanaian, J Gupta, A Revi, N Sami & C Tortajada (2023). Goals, progress and priorities from Mar del Plata in 1977 to New York in 2023. Nature Water https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00041-4

An author’s draft of the paper can be downloaded free at

(PDF) FromMardelPlatatoNYC Jan2023 (researchgate.net)

Also available are a collection of stories in Nature Water on the UN Water Conference 2023 available free to access for 2 weeks, starting March 13, 2023

https://www.nature.com/collections/jggcdacijj

R. Quentin Grafton is a Professor of Economics at the Australian National University (ANU), Convenor of the Water Justice Hub, and a Lead Expert and Commissioner of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water. He is also the Executive Editor of the Global Water Forum.

Asit K. Biswas is a Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Hilmer Bosch is a Postdoctoral Researcher Global Commission on the Economics of Water, University of Amsterdam.

Safa Fanaian is a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Crawford school of Public Policy at the Australian National University (ANU).

Joyeeta Gupta is the Professor of Environment and Development in the Global South at the Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research of the University of Amsterdam and IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, and a Lead Expert and Commissioner of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water.

Aromar Revi is the Founding Director of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) and a Lead Expert and Commissioner of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water.

Neha Sami is Associate Dean, School of Environment & Sustainability and Senior Lead, Academics and Research at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements.

Cecilia Tortajada is a Professor, School of Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom.

This article was published by GLOBAL WATER FORUM, March 14, 2023.