Chetan Pandit and Asit K Biswas

THE TIMES OF INDIA | March 22, 2019

Today is World Water Day. It is imperative that politicians and general public do some soul searching on the impacts of poor water management for decades on the country’s future social and economic development.

Take its National Water Policy (NWP). India was a pioneer in developing NWP in 1987, when such a policy was rather uncommon. Since then the Indian NWP has been revised twice, in 2002 and in 2012. However, more than 30 years after the first NWP, far from helping India in modifying her water management practices to achieve the desired social, economic and environmental outcomes, successive NWPs have had no impact whatsoever on water management.

Driven by a compulsion to be politically correct, while also being influenced by fashionable ideas paraded in international water seminars, all the versions of NWPs have promoted ideas that are un-implementable in the Indian context. For example all the NWPs have endorsed basin as a unit for all planning, and have recommended establishment of River Basin Organisations (RBOs) as the platform where all the stakeholders in a basin are represented, and where such basin planning can be done. NWP 2012 went a step further and stated that comprehensive legislation needs to be enacted to establish RBOs. However, after three decades of espousing basin as a unit for all planning, no basin is being planned or developed thus, and there isn’t even one inter-state RBO.

Inter-state river water disputes are resolved by specially constituted Tribunals which allocate water shares to various states, based on juridical principles of riparian rights, prescriptive rights, and equitable distribution. Each of these principles, though a valid legal principle, divides the basin and its water resources in several independent parts, and therefore contradicts the idea of basin planning.

“Integrated Water Resources Management” (IWRM) is another such lofty idea remaining on paper. IWRM has been around as a seductive concept for at least 70 years, but during this period not even one single moderate size river has been planned in an integrated manner anywhere in the world. The entire NWP text is strewn with superfluous words, and suggestions that are sound but not specific and therefore of no real use.

This lack of commitment is seen even in the style of prose of all the three versions. Clause 5.1 of NWP 2012 says, “The availability of water resources and its use by various sectors in various basin and States in the country needs to be assessed scientifically.” Water resources assessment is entirely within the jurisdiction of ministry of water resources (MoWR); an assessment does not need enactment of any legislation, nor any approval from Parliament, or from the states; and mere assessment will not lead to any political fallout. Then who is the intended recipient of the advice that the water resources need to be assessed scientifically? Instead of giving homilies, why doesn’t the MoWR just go ahead and do it?

A policy statement has to emerge out of, and has to be backed by, sound policy research. But the NWPs have consistently contained ideas that were clearly not based on policy research. A glaring example is the support to Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in the water sector. Clause 13 of the NWP of 2002 made a very emphatic statement for the PPP, recommending all models of PPP, for example management, BOT, BOOT. But after 10 years, there wasn’t a single irrigation project in PPP mode.

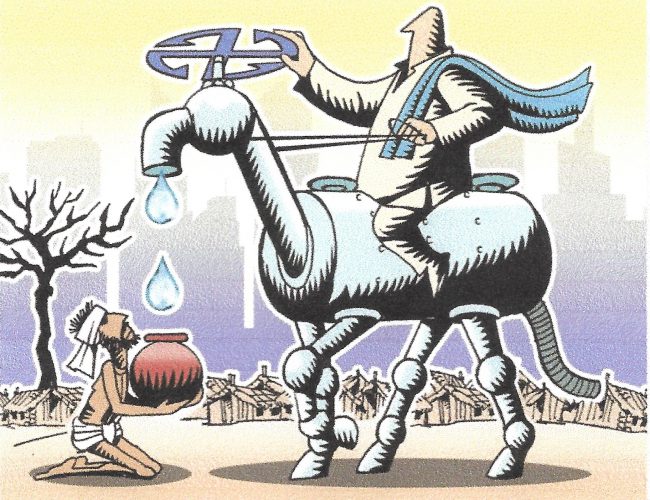

Civil society organisations had raised some valid concerns, such as how the interests of the poor will be protected; how the private sector operator will be prevented from gaining undue control of water at source; will it become a case of private profits and public risks; who will decide the tariffs, and on what basis. The water bureaucracy had no answers, and the NWP 2012 quietly removed this emphatic support for PPPs.

Despite having a written NWP for more than 30 years all the problems, be it water scarcity, deteriorating quality, aquifers being sucked dry, inter-state disputes and now even intra-state disputes, are only increasing. NWP 2012 is now seven years old. Here are a few practical suggestions for the next revision of NWP, whenever it is taken up.

All those who are party to formulating the NWP, need to accept that policies are a set of guidelines for decision making, to steer outcomes towards some stipulated objectives. Therefore policies have to be realistic, and not merely a lofty statement of how a nation wishes things to be. Therefore, the next NWP must be based on policy research. The language should be more assertive. It should clearly stipulate what is necessary, how it will be achieved, who exactly will do what, within what time frame, and what preceding actions are a prerequisite to do it.

India’s water management has been on an unsustainable path for decades. Our politicians have managed water mostly for short-term electoral gains and not for long-term benefits of the country. It is now facing a water crisis in terms of quantity, quality, magnitude and severity which no earlier generation ever had to face. Sadly, there are no signs that our politicians have realised the severity of the situation the country is facing and are willing to take some hard decisions. If the current trends continue, India’s water crisis will only worsen with time.

Chetan Pandit is former member of Central Water Commission. Asit Biswas is Chief Executive, Third World Centre for Water Management, Mexico.

This article was published by THE TIMES OF INDIA, March 22, 2019.