Preeti Jha

BBC | August 22, 2018

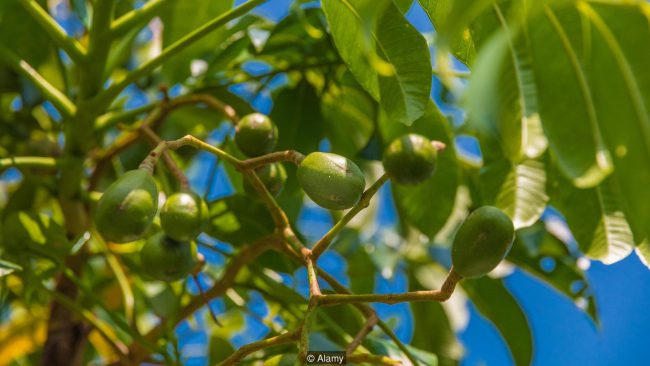

On a small fruit farm near the Straits of Malacca Lim Kok Ann is down to just one tree growing kedondong, a crunchy, tart berry that Malaysians mostly use in pickles and salads. “It’s not very well-known,” says the 45-year-old, who is instead focusing on longan berries and pineapples, which have bigger markets. For a smallholder like Lim, demand for kedondong would have to grow rapidly to justify scaling up his business. “We have to grow what is profitable,” he says.

But less than an hour away in the Malaysian countryside, inside three giant, sleek and silver domes, scientists are trying to change the future of food. They’re pushing the boundaries of what humans eat by growing and processing so-called ‘alternative’ crops – such as kedondong.

At the headquarters of global research centre Crops For the Future (CFF) this particular under-used fruit has been turned into an effervescent, sugar-free juice, high in vitamin C and getting top marks in sensory evaluations.

“Anything you see here is a forgotten crop,” says Sayed Azam-Ali of the abundant plants weaving through the gardens of CFF outside Malaysia’s capital Kuala Lumpur.

Spindly moringa trees, cream-coloured bambara groundnuts, the sour kedondong berry – these are crops which have been farmed for centuries but are virtually unknown outside the places where they grow. Even here, demand is dwindling. They’ve been relegated to the sidelines, says CFF head Azam-Ali, in favour of the “big four”.

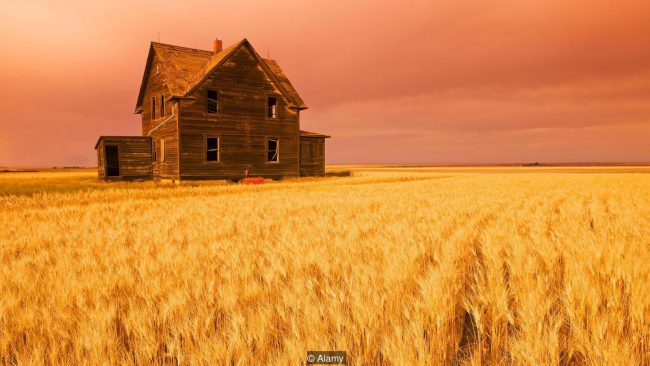

Prof Azam-Ali explains that just four crops – wheat, maize, rice and soybean – provide two-thirds of the world’s food supply. “We’re dependent on these four,” he says. “But actually there’s 7,000 crops we’ve been farming for thousands of years. We ignore all of those.”

Researchers are trying to unlock the potential of these ignored crops – plants they describe as forgotten, under-used or ‘alternative’ as they are displaced by increasingly uniform diets fuelled by processed ingredients from the major crops.

It’s a timely quest. The food sector is already responsible for nearly a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation. By 2050 it estimates the world must produce 50% more food to feed the projected global population of 10 billion. Meeting this demand without contributing to climate change, further eroding biodiversity and causing yet more damage to ecosystems calls for urgent solutions.

Forgotten crops hold key answers, according to CFF. By investing in neglected local plants, countries can reduce their reliance on imported crops and their carbon-heavy supply chains. Reclaiming the variety of crops humans once ate also boosts food security at a time warming climates threaten existing crops. On top of that forgotten crops are among the most climate-resilient and nutritious, argues Azam-Ali. His summary is plain: “Dietary diversification is critical to the future of humanity.”

Food security experts agree. “There is no food insecurity in the world, there is food ignorance,” says Cecilia Tortajada, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Water Policy at the National University of Singapore. “Whenever we have indigenous crops we tend to disregard them as if they were not valuable but they are,” she adds.

Azam-Ali knows that scepticism firsthand. He came across alternative crops in the 1980s through the work of women farmers he met in Niger. The then-PhD student remembers marvelling at the crops they grew in their backyards, without the benefits of technology, to feed their families when the big crops failed. He saw a tremendous opportunity to build alternative food systems. But “the resistance was enormous”, he recalls.

Undeterred, he ploughed on. Project after project helped prove these crops were viable in different environments as alternatives to the staple ones. But the question of whether these crops would be marketable remained. “That’s the critical thing. What is the end use going to be?” he says.

In one of the centre’s domes, food technologist Tan Xin Lin whips up a bright green batter. Using powdered moringa leaves in place of some wheat flour, she is trying to bake a cake lower in gluten and higher in nutrients.

Xin Lin’s job is to concoct recipes with these still-unfamiliar ingredients that will appeal to both local and international palates. In recent years she has used some of the forgotten crops grown at CFF, such as moringa and bambara groundnut, to make everything from instant soup and Italian biscotti to tortellini and murukku, a crunchy Indian snack usually made from chickpea flour.

“I try to modernise forgotten crops instead of using old recipes,” says Xin Lin, who is also a trained patisserie chef. It’s a strategy to appeal to the world’s growing middle classes who are increasingly turning to the fast and processed food industries. It’s also a way to help counter perceptions of local crops as “old or poor people’s food” or as inferior “women’s crops”, adds Xin Lin.

The roots of these connotations about local foods can run deep. The bambara groundnut, a protein-rich legume native to sub-Saharan Africa that is also grown in parts of southeast Asia, can trace its marginalisation to colonial rule. “African women who grew bambara groundnut were actually punished for growing it,” says Azam-Ali. “Colonial powers said you can’t grow that because there’s no oil. We can’t get a market for it.”

But today the bambara murukku is one of CFF’s best reviewed foods and they are aiming to get it into grocery stores, pointing to the success of crops like quinoa to potential investors. Some 30 years ago, quinoa was virtually unheard of outside its native mountains in Bolivia and Peru. Today the nutritious grain is found on the menus of plush eateries across the world.

Measuring crops by nutrition instead of yield is at the heart of the forgotten foods enterprise. Ever since the “green revolution” of the 1960s, high-yielding crops have dominated modern agriculture. That was in part a crucial response to devastating famines at a time when the world needed to increase its food supply. Today “nutrition is becoming a time bomb”, says Azam-Ali, as growing carbon dioxide levels strip crops of their minerals. Instead of bio-fortifying major crops we should be investing in those forgotten crops that are already more nutritious, he asserts.

In the bowels of CFF’s third dome, lab manager Gomathy Sethuraman opens a window into the centre’s “crown jewels”, revealing vines of winged beans growing under a bright yellow light. It’s one of multiple chambers where scientists are studying the impact of higher temperatures and carbon dioxide levels on the nutritional make-up of alternative crops. This research is “the game changer”, says Azam-Ali, ensuring that ‘future crops’ are also the healthiest ones in warmer climates.

There is a growing global momentum around forgotten foods, says Danielle Nierenberg, president of Food Tank, a US-based think tank. Other than CFF, which bills itself as the world’s first research centre dedicated solely to underutilised crops, there are other key groups championing agricultural diversity including Crop Trust, Slow Food, Icrisat and Bioversity International. Add to that more middle-income consumers searching for nutritious foods and others eager to try the unprocessed foods their grandparents once ate, she says.

Underpinning the movement are farmers themselves. “This is something farmers, especially women, have been doing for as long as agriculture has really existed,” says Nierenberg. “They’ve been saving seeds, trying to reserve crops their families are actually eating. That’s preserving a lot of agricultural biodiversity and making sure these crops are passed from generation to generation.”

But the rising interest in forgotten foods in some quarters is outpaced by the global spread of Western-style diets heavy in sugar, fat and processed foods in others.

A key obstacle for bringing fading local crops to the fore in Malaysia, for example, is “the obsession with imported products”, says Jenifer Kuah, co-founder of a restaurant that champions locally-sourced food in an affluent suburb of Kuala Lumpur. Customers at Sitka, regarded as a pioneer in the country’s small farm-to-table dining scene, still seek foreign ingredients as a “status symbol”, she says.

When they serve up local vegetables such as winged beans, Kuah says it’s about “re-envisioning the product, not doing it the same way, as people want something new”. Her observations echo those of food technologist Xin Lin, as both work to overturn old food habits.

The argument for forgotten foods feels intuitive. Some analysts say it is in fact inevitable. “Climate change is going to mean almost certainly tastes are going to be forced to change,” says Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City, University of London. We “have to get used to eating other crops” as yields of staple crops fall, he says.

Yet persuading private-sector investors to back alternative crops remains a mammoth challenge. “They’ve all been here,” says Azam-Ali when asked if big industry has been receptive. He won’t name who but adds they “say it’s very interesting but there’s no market”.

Key to CFF’s strategy now is engaging people with their own forgotten foods to help in turn generate a demand for them. Last November they invited Prince Charles to launch their Forgotten Foods Network, a resource to collect disappearing recipes worldwide that then offers another opportunity to turn to local crops.

“These forgotten foods are in all of our family histories,” says the CEO. “If we don’t store the knowledge, that’s 10,000 years of history, gone in one generation.” He’s determined to make sure that doesn’t happen.

This article was first published by BBC, August 22, 2018.