Asit K. Biswas and Cecilia Tortajada

THE STRAITS TIMES | March 22, 2017

On World Water Day today, it is appropriate to reflect on the future of Singapore’s water.

The Singapore Government announced recently that the price of water will be increased in two stages. Mainstream and social media have been full of comments on its need, relevance and appropriateness.

Singapore last increased its water price in 2000, and thus, for 17 years, this price has remained constant. Almost a generation has grown up with no adjustment in water price. Electricity rates are significantly higher than those for water; they are adjusted regularly. Thus, whenever electricity rates are modified, there is seldom a ripple and it is not big news. However, when the water price is increased after 17 years and heftily so, it became a big news item.

The water price increase will be ameliorated greatly with increases in the value of the goods and services tax (GST) voucher. Families in one- and two-room HDB flats will receive $380 of U-Save rebates each year compared with $260, and families in three- and four-room HDB flats will receive $340 and $300 per year respectively, compared with $240 and $220. Consequently, on average, there will be no increase in the water bills for people in one- and two-room HDB households.

Consider some facts.

First, unquestionably, national water agency PUB has been an incredibly efficient institution. It has managed to increase its operational efficiency steadily so that it could balance its books until 2010, when it last made an operational profit of $48 million. From 2011, it has been making operating losses, which had to be made up by government grants. PUB losses have increased from $36 million in 2013 to $57.2 million in 2015.

Our studies indicate that between 2000 and 2014, because of inflation, water price decreased by 25.48 per cent in real terms. In contrast, electricity and gas prices have increased at a rate slightly higher than inflation.

In addition, the median income of employed resident households was $4,398 in 2000. This increased to $8,292 by 2014. Thus, assuming a household used 20 cubic m of water per month in 2000, the household’s water bill represented 0.69 per cent of income. By 2014, it had declined to about 0.36 per cent.

Not surprisingly, a recent poll by The Straits Times showed that 75 per cent of Singaporeans had no idea what their water bill was.

FEAR DROUGHTS, NOT FLOODS

Singapore now needs to change the narrative from an argument of cost recovery for domestic and industrial water supply to one of managing a scarce, strategic and essential resource. For this, a profound societal mindset change is necessary as to how water should be managed in the future.

Let us assess the current situation. At present, about 50 per cent of water used in Singapore comes from Johor. Due to the recent prolonged drought, storage at Johor’s Linggiu Reservoir late last year was at a historic low.

On Jan 9, Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said in Parliament that there is a “significant risk” that the reservoir may not have any water if this year turns out to be dry. Fortunately, the storage is now more than 30 per cent, but nothing assures us that this may not change again in the coming months or years.

If Linggiu dries out, Singapore will lose not only half of its water supply, but there may also be a significant reduction in its Newater production. Newater is high-quality recycled wastewater. If the supply from Linggiu is cut by half, how would this affect wastewater generated and, thus, Newater production?

Add to this the potential uncertainty imposed by climate change, which is likely to contribute to prolonged droughts, as witnessed in many parts of the world.

Accordingly, the prudent strategy for Singapore will be to prepare for the time, not if but when, the supply from Linggiu will reduce to a trickle due to prolonged drought. In the last six years, we have regularly argued that it is not floods but droughts that Singapore needs to fear.

MAKE DRASTIC CUTS IN WATER USE

Current estimates suggest that by 2050, Singapore will need significantly higher amounts of water than what it currently consumes. Accordingly, efficient water management must receive priority national attention.

Even at current rates,domestic and industrial water usage is far too high for comfort. Both need to be reduced very significantly by judicious use of pricing, economic incentives, public education, awareness and, above all, behavioural changes.

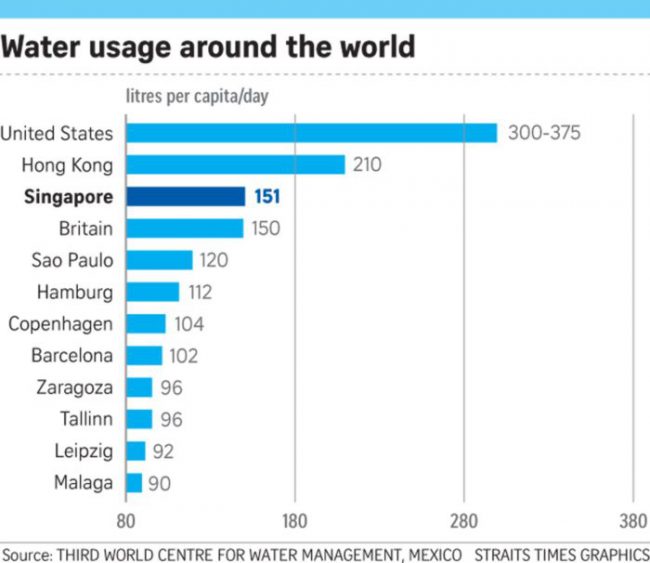

Take domestic water use. In Singapore, domestic water consumption is over 50 per cent more than that in many other efficient cites. Per capita daily consumption in Singapore is about 150 litres. In contrast, developed cities like Malaga, Tallinn, Leipzig and Zaragoza have managed to reduce their per capita water consumption to less than 100 litres (see graph below).

In the developing world, Sao Paulo reduced the average per capita daily consumption by an innovative pricing structure and good public awareness campaigns. If Paulista households reduced their water consumption compared with their use between February 2013 and January 2014, they received a generous rebate. If the reduction was between 10 per cent and 15 per cent, the rebate was 10 per cent. If it was over 20 per cent, the savings were 30 per cent. Concurrently, if households used 20 per cent more than the average, they had to pay a surcharge of 40 per cent. These actions reduced Sao Paulo’s per capita water consumption from 143 litres in 2014 to 120 litres by 2015.

True, these cities are in different climates and lifestyles do differ. However, water conservation practices are what counts, and a combination of economic instruments, and attitudinal changes by developing a conservation ethics, ensured a more efficient use of water.

Singapore’s current target is to reduce per capita water consumption to 147 litres by 2020 and to 140 litres by 2030. This, in our view, is too little, too late. The city-state should be much more ambitious.

Between 1960 and 1970, Singapore carried out a unique study as to how much water an individual needed to lead a healthy life. It showed that at levels above 75 litres per day, there were no health benefits. An average Singaporean now uses twice this amount. Given that many European cities have progressively reduced their daily water consumption to less than 100 litres, Singapore needs to consider a much lower target of around 110 litres per day by 2035, which is achievable. By 2035, people in the most water-efficient cities will be using around 85 litres per day.

Finally, a mindset change is needed in terms of benchmarking good practices. Major technological breakthroughs often come from the developed world. However, many of the most significant policy breakthroughs are coming from the developing world. For example, Namibia’s Windhoek has had direct potable use of treated wastewater for nearly 50 years. In the city of Jaipur, India, people know from their regular water bills how much public subsidies they are receiving.

Most Singaporeans in contrast do not know how much they pay for water, let alone that they do not pay for all of their water-related services themselves, as some are borne by the state. For example, the Government pays for all stormwater management services as public goods, which households in numerous cities pay directly through their water bills.

Given the strategic importance of water in Singapore, it is essential to engage the population in the formulation of future policies through a robust communication strategy with all the facts, figures and implications of possible decisions. This will ensure its water security for decades to come.

Professor Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, where Dr. Cecilia Tortajada is Senior Research Fellow at its Institute of Water Policy.

Source: http://bit.ly/2mNJuTa