MEGA | July 8, 2016

Every morning, in a small town located just an hour’s drive from some of the world’s biggest freshwater lakes, a long line of vehicles snakes out of a fire station, each passenger queuing patiently for their daily allowance of clean water.

Eight thousand miles away, the residents of a city lying at the lower reaches of one of the largest delta regions on Earth count themselves lucky if they get running water for more than a few hours per day.

Worlds apart they may be, but the experiences of Flint in the US, where drinking water was poisoned after a botched cost-cutting drive, and Kolkata, the Indian metropolis, are manifestations of the same problem, says Professor Asit Biswas, founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management.

And that problem, he explains, is an ingrained disregard for how water should be distributed, treated and consumed.

“We are not dealing with water scarcity here but mismanagement,” he explains. “The case of Flint has shown how neglecting issues such as operation and maintenance for decades will invariably come back to haunt you – there is a political, social and an economic price to pay.”

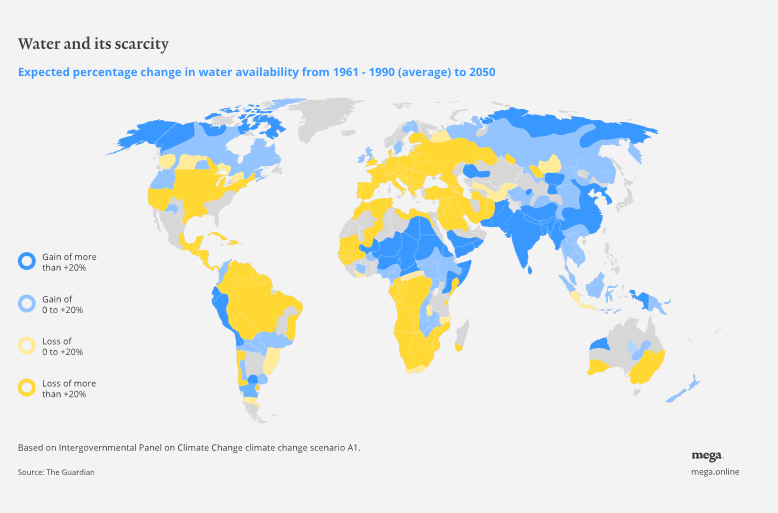

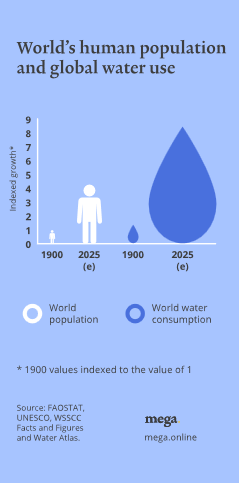

Even before the Flint debacle, water was a byword for crisis. Business organisations such as the World Economic Forum have described water shortages as the biggest risk to the planet, while religious leaders including Pope Francis I have added their voices to calls for governments to do more to tackle water scarcity. In the emerging world alone, it is estimated that up to 3 billion people do not have regular access to water, while the UN estimates up to 40 per cent of the world’s population could be facing severe water scarcity in less than 30 years.

There is no simple solution to these problems, Prof. Biswas explains.

MORE INVESTMENT, BUT HIGHER PRICES

Progress needs to be made on several fronts. An essential first step is securing much needed investment to fix inadequate and leaky water supply networks.

“London’s sewerage network was designed 150 years ago, while in the US, some pipes were laid during the Civil War,” he says. What’s more, he explains, these systems have been neglected for years.

In the US, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that catching up with the backlog of repairs and upgrades of underground pipe systems would require investing more than USD1 trillion. In South America and Asia, meanwhile, it is estimated that water infrastructure needs some USD14 trillion of new investment over the next decade.

But where will that money come from?

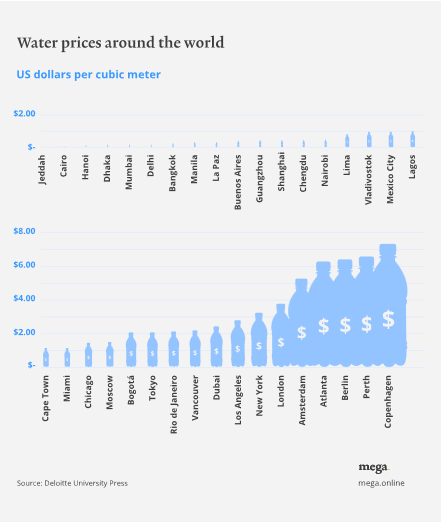

Much of it could come from consumers, Prof Biswas says. Water, he believes, should command a much higher price at the point of use. Currently it is mostly provided free or highly subsidised to households in both the developed and developing world. Only when the cost of use rises to reflect water’s true value will water management become economically viable.

“Find the right price, and the right way to nudge consumers, and this will deliver the stable revenue required to make the necessary investment,” he says.

This might initially prove tricky to pull off in emerging nations as households there are reluctant to pay more for mains water that is of consistently poor quality. So improving the quality must come before higher charges.

“To convince consumers, companies can provide the first two years’ worth of water for free and improve piping and meter all the houses. After 18 months, the companies can then provide bills so people are aware of their consumption,” Prof Biswas says.

Higher water prices and more prudent use of water would go a long way towards cutting waste.

Protecting the planet’s water resources could become easier still if technological and scientific innovation gather pace.

BETTER TECH, BETTER ECONOMICS

A promising area of research is in water desalination. Scientists believe nature could hold the secret to turning ocean water in to fresh water, which is currently a very costly and energy-intensive process.

They are studying the mechanism through which mangrove swamps and anadromous fish species such as salmon process the salt in saltwater, in the hope of improving current desalination techniques. This could become a significant way to combat fresh water shortages.

Another area where knowledge could make significant difference is in behavioural economics. “For example,” Prof Biswas asks, “why does an average Qatari citizen uses 1,200 litres per day whereas an ex-pat in Qatar uses less than 20 per cent of this amount? And why does Tokyo lose less than 4 per cent of its water?”

These are questions to which only behavioural economists can provide answers. But the problem, he explains, is that expertise in this field is thin on the ground.

“Sadly, the number of behavioural economists working in the entire world can be counted on the fingers of one’s hands, and still have some fingers left over!”

Even so, Prof Biswas remains optimistic.

From technology to finding the right price and the right way to nudge consumers, we have tools to combat the risk of water scarcity. “It is up to governments to ensure they are used.”

Prof. Asit K. Biswas is the Founder of Third World Centre for Water Management and Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School for Public Policy in Singapore. He is a recognised authority in the field of water and natural resources management and has advised businesses, national governments and UN and other international agencies. He is a recipient of the Stockholm Water Prize, considered the Nobel Prize for water.

Source: http://bit.ly/29mCBWV