Siau Ming En

TODAY | April 23, 2016

The Republic’s success in turning its vulnerability in water into a strength within four decades has been well documented. But the drought across the Causeway is raising serious concerns here: With the water level in Linggiu Reservoir in Johor rapidly falling to historic lows, the scenario where Singapore would be unable to import any water from its neighbours before the Republic becomes self-sufficient in 2060 is not as far-fetched as it may seem, experts say.

Built in 1994, the Linggiu Reservoir enables Singapore to reliably draw water from the Johor River by releasing water into the river to prevent saltwater intrusion from the sea into the river.

Salty water cannot be treated by the water plant further downstream from the reservoir.

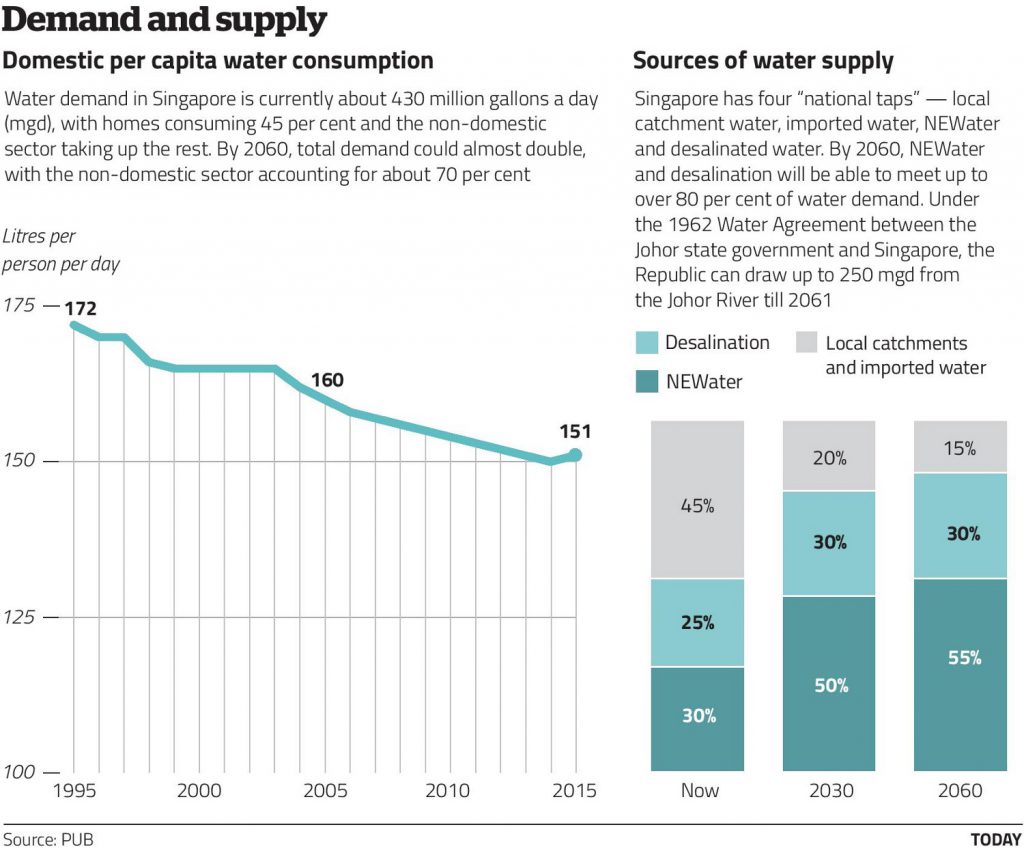

Currently, water from Johor River helps to meet half of Singapore’s water needs. Under the 1962 Water Agreement between Singapore and the Johor state government — which expires in 2061 — Singapore can draw up to 250 million gallons of water per day (mgd) from the river.

On Friday (April 22), the water level at Linggiu Reservoir fell to yet another historic low of 35 per cent — down from 36.9 per cent about 1.5 weeks ago, the PUB said in response to TODAY’s queries. The level has fallen dramatically over the past year or so: At the start of last year, it was about 80 per cent. Eight months later, it receded to 54.5 per cent. This dropped further to 43 per cent in November last year, before falling to new lows in recent days.

Professor Asit Biswas, distinguished visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), said: “(In the) short term, I don’t see any problems unless there is a prolonged drought … The only problem with nature is that it is so uncertain to predict.”

He added: “So if you have a prolonged drought for five, six months, it is very unlikely there will be any significant amount of water coming from Malaysia … That could happen any day, it could happen from tomorrow, it could happen 40 years from today … And that is without (factoring in) climate change; that is simple climatic fluctuations that we have witnessed in the past.”

While Singapore and Malaysia enjoy good relations and have a treaty in place, Prof Biswas noted that the supply of water from Johor can by no means be taken for granted. Prof Biswas, who won the Stockholm Water Prize — considered the water industry’s Nobel Prize — a decade ago, noted that there is a high probability of the region experiencing a serious drought in the coming decades.

And if that happens, “would the politicians and people (in Malaysia) be willing to send that water to Singapore or say it’s an act of God, they really cannot send water and they need to use it themselves? I don’t know”, he said.

Apart from imported water, Singapore has three other “national taps”: Local catchment water, NEWater and desalinated water.

Singapore could become self-sufficient in water by 2060, a year before the water agreement with the Johor state government expires. By 2060, NEWater and desalination will be able to meet up to 85 per cent of water demand.

Efforts are under way, including ramping up the purification of treated water — to produce NEWater — to meet more than half of the country’s water needs.

Currently, NEWater can meet 30 per cent of Singapore’s total daily demand of 430mgd. By the end of the year, Singapore’s fifth NEWater plant will be up and running.

Supply of desalinated water or treated seawater will also be increased. Singapore has two desalination plants that can produce a total of 100mgd of water to meet almost 25 per cent of the demand. By 2030, this will go up to 30 per cent. A third desalination plant in Tuas is due to be completed next year, while the fourth desalination plant in Marina East will be built by the end of 2019.

The Government recently announced it was looking at building a fifth desalination plant on Jurong Island.

Singapore also collects rainwater through a network of drains, canals, rivers and stormwater collection ponds before it is channelled to the 17 reservoirs across the island for storage. The country’s water-catchment areas currently take up two-thirds of the island and PUB hopes to expand this to 90 per cent by 2060.

A ONE-OFF EVENT OR A SIGN OF THINGS TO COME?

The jury is still out on whether the changes in weather patterns are due to climate change or the El Nino phenomenon, which comes along every two to seven years.

El Nino refers to the abnormal warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean, which can potentially wreak havoc on weather conditions. In the case of South-east Asia, it can lead to prolonged drier and warmer weather.

Dr Cecilia Tortajada, a senior research fellow at the LKYSPP Institute of Water Policy, said: “We don’t know (whether) what is happening now or even the last year … could be a trend. It could be a climatic event related to El Nino but not necessarily (in line) with these big trends that may change completely the patterns of rainfall in Singapore.”

Dry weather conditions in the region were worsened by El Nino, which developed in the middle of last year and is gradually weakening. Still, regardless of the underlying causes, the impact of extreme weather on a small island-state such as Singapore is significant, she said.

“Singapore is very small, so that means that … if there is less rainfall, then it’s going to impact the entire land and the entire surface that is used for the reservoirs,” said Dr Tortajada. “The amount of water we have in Singapore as a tropic city-state is very high. But if you have less rainfall, it will have an impact because we don’t have any other sources (apart from NEWater and desalinated water). There is no snow, for example. So if it rains less, it’s going to affect everybody.”

PUB deputy chief executive (Policy and Development) Chua Soon Guan told TODAY that climate change is not the only factor affecting the national water agency’s long-term planning. “We have to look at a whole set of other considerations, in terms of land constraint, in terms of national development and so on to see what is best for Singapore. Also, resilience is not just against climate change, we want to be resilient against all sorts of contingencies. So (the) question is, which source is more resilient? That part we do have to think through,” he said.

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE COULD AFFECT WATER SUPPLY

Just last week, Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli spoke about his “personal worry” that the extreme weather patterns due to climate change would pose new challenges to Singapore’s water sustainability.

Dr Rajasekhar Balasubramanian, from the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, noted that climate change could affect the intensity and frequency of rainfall, where dry spells get drier and wet seasons wetter. Rising temperatures would also mean more water evaporating, thus affecting the water levels in the Linggiu Reservoir as well as Singapore’s water-catchment areas, added Dr Balasubramanian.

As the weather becomes warmer, water temperatures will also rise in tandem. This could lead to the thermal stratification of water, which prevents the mixing of waters, resulting in the accumulation of chemical pollutants and potentially causing algal bloom. Heavier rainfall will also lead to greater runoffs that can carry with them chemical and biological pollutants or suspended particles. All of these could lower the quality of water collected in local catchments, making it more costly for Singapore to treat surface water, added Dr Balasubramanian.

A key challenge of climate change is the adequacy of water supply during periods of dry weather, said Professor Ng Wun Jern, executive director of Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute at the Nanyang Technological University. “Our reservoirs collect water from surface runoff — (for example) rivers. So if there is a dry spell, surface runoff shrinks and less gets into the reservoirs,” he said.

While Prof Ng felt that the dry weather will have little effect on water reclamation and practically no effect on desalination — since the sea is an “infinite” water source — Dr Balasubramanian noted that the quality of coastal waters could be affected with longer dry spells.

There could be a higher concentration of chemical pollutants and microorganisms in the coastal waters, which will require the authorities to enhance the capabilities and technologies being used for desalination to meet the stringent standards for drinking water, added Dr Balasubramanian.

INCREASING SUPPLY

Singapore’s current water infrastructure was planned around, among other information, the projections from the first phase of the Second National Climate Change Study. “The planned infrastructure is to cater for a certain set of weather scenarios, then we are confident that whatever we have planned for, we are resilient against these scenarios,” Mr Chua said.

On climate change, he noted that it does not occur suddenly. “So far it’s not a disruptive change, as far as what we understand … (but) it’s important that we review and update our planning assumptions regularly,“ he said, adding that PUB could not predict all possible scenarios caused by climate change.

For existing water infrastructure and systems to better handle the effects of extreme weather, the experts TODAY spoke to raised various ideas to improve Singapore’s water technology and management.

PUB is currently looking into other desalination technologies, including electrodeionisation, where ions carrying either a positive or negative charge are separated from the water when they are attracted to electrodes of the opposite charge.

It is also studying biomimetic and biomimicry techniques. An example is the development of a biomimetic membrane that has high permeability to water but rejects organic molecules and salts.

Assistant Professor Pat Yeh from NUS’ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering suggested that more water could be collected from local catchments. This can be achieved by expanding or deepening the current reservoirs, he said. Instead of letting large volumes of water flow over the surface before storing it in reservoirs, Dr Balasubramanian proposed harvesting rainwater directly, such as on roofs, to use it for non-potable purposes.

He also suggested the idea of decentralised or cluster water-treatment systems, which would collect rainwater at different locations, treat them and use them at the same place concurrently. This would remove the need to transport the water through pipes and improve cost-effectiveness, added Dr Balasubramanian, who has done preliminary research in this area. He noted that a decentralised system will allow different treatment facilities to be set up according to the needs of the areas, which may not all require high-quality water.

PUB has previously said it is studying the possibility of drawing on “naturally occurring aquifers and groundwater” in western and eastern Singapore — possibly creating the fifth national tap. Aquifers are underground layers of water-bearing permeable rock or unconsolidated materials, such as sand, from which groundwater can be extracted.

‘DO MORE TO REDUCE DEMAND’

Instead of looking for new sources of water supply, Prof Biswas and his wife Dr Tortajada felt that Singapore should do much more to reduce

demand.

“It’s the missing tap, the tap that (Singapore is) not considering very seriously,” Prof Biswas said. He added: “If you reduce demand by 1 cubic metre, that means you do not have to produce 1 cubic metre of water.”

Last year, Singapore’s per capita domestic water consumption inched up to 151 litres per day, from the 150 litres in 2014. It also bucked the downward trend of per capita domestic water consumption since 2004. The Government’s target is to reduce the figure to 140 litres by 2030.

Prof Biswas said: “There are, of course, countries (that use) much more than Singapore, but Singapore cannot afford to do that because 50 per cent of its water is still coming from Johor.”

He felt that the 2030 domestic consumption target was “too conservative”, citing how some European cities such as Barcelona and Zaragoza have, for several years now, reduced their water consumption to less than 100 litres each day. Singapore should strive for a target of between 110 and 115 litres per day, he added.

To reduce water consumption, some experts, including Prof Biswas, have suggested raising water prices. But others disagree, citing the low price elasticity of water.

In Singapore, water is priced to recover the full cost of its production and supply as well as to reflect its scarcity value. The price has remained the same since 2000.

Currently, households pay about S$1.93 per cubic metre, including Goods and Services Tax (GST), for those using 40 cubic metres of water or less per month. They also have to pay a sanitary appliance fee of S$3 (including GST) per appliance each month.

Prof Biswas said: “A vast majority of Singaporeans haven’t (got) a clue what their water bill is. They know their electricity bill. You ask anyone what is their water bill, 90 per cent will have no idea … because it’s so little.”

He added: “Everything else has gone up, electricity prices have gone up, but the water prices have remained the same.”

Agreeing, LKYSPP vice-dean (Research) Eduardo Araral noted that water prices here have not been adjusted for inflation. In real terms, Singapore’s water prices have declined by 25 per cent over the years, he said.

“Increasing water prices is basically buying insurance against climate change,” he said. With more extreme weather, greater energy will be used to produce more NEWater and desalinated water. “Somebody’s got to pay for that,” he pointed out.

He added that prices should reflect the scarcity of water, such as factoring in the cost of building and operating new desalination plants. He noted that PUB has been trying to improve conservation of water through education and engineering solutions, among other things. “In the past 15 years, those efforts are no longer enough to convince people to reduce consumption,” said Assoc Prof Araral.

But water economist Joost Buurman stressed that changes in water prices would not make a big difference in consumer behaviour. “The price elasticity of water is very, very low, so you need to increase the price very drastically for people to use less water,” he said.

Pointing out that water bills make up a very small proportion of the average Singaporean household income, Dr Buurman said a slight reduction in consumption would only affect a household’s water bill by “50 cents or a dollar”. Most people “won’t be bothered”, said Dr Buurnam, although he acknowledged that raising the price of water would have a “psychological effect” on people.

Prof Biswas pointed to how charging for the use of plastic bags at supermarkets in the United Kingdom has succeeded in reducing usage, even though the charges do not add up to much. “We are not having a discussion on these (behavioural) issues,” he said.

Singapore might also want to consider incentives to get people to conserve water, suggested Prof Biswas. The Spanish public utilities department, for example, would reduce a household’s utility bill by 10 per cent for a corresponding cut in water consumption, he said. “The focus in most parts of the world, including Singapore, has been on technology … We now have to think of how to modify human behaviour,” he added.

PUB’s Mr Chua said that as desalinated water and NEWater meet more of the country’s water needs, the cost composition — including energy, manpower, land and capital — may be affected. “I don’t think we can say that climate change will cause the price to change, we have to recognise other factors. Even though now energy price is on the low side, you’ll never know, it can go up,” he said. “If it goes up, then our cost will go up.”

Alluding to the prevalent view that Singapore is a victim of its own success when it comes to water, Dr Buurman noted that PUB “is always very careful in letting people have the confidence that we can handle any bad situation”.

But the Government should also prepare Singaporeans, who are “always very much in a comfort zone”, for the worst-case scenario.

With Linggiu Reservoir drying up, the message could not be starker. “What if Linggiu Reservoir dries up and there won’t be any rainfall or very little rainfall for a few subsequent years?” Dr Buurman questioned.

He added: “(What) happens during dry periods is that people actually start using more water — they want to water their plants and maybe take more showers because it’s hot. So that is actually the opposite of what you should do during a drought.”

Indeed, when the worst-case scenario strikes, Singaporeans’ behaviour and water-consumption habits could be brought to a test — and as the experts point out, hopefully it would not be too late then.

This article was published by TODAY, April 23, 2016.