Asit K. Biswas and Kris Hartley

THE STRAITS TIMES | April 24, 2015

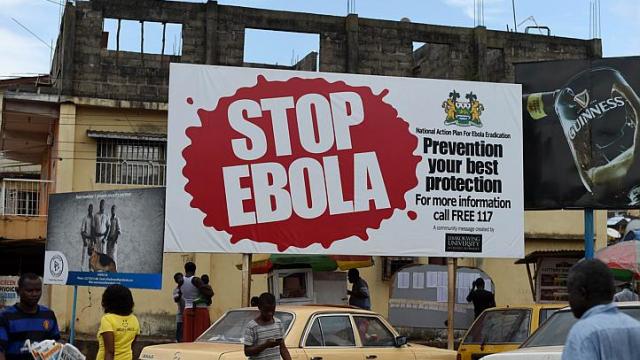

West Africa is slowly recovering from history’s deadliest Ebola outbreak, which to date has claimed more than 10,000 lives. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has received sharp criticism for its slow and inept response. Critics deride the agency’s weak leadership, “arcane” organisational structure, and drifting strategic focus.

A New York Times editorial argued that funding constraints and weak authority over member nations continue to hamstring response preparation. WHO has announced a series of reforms, but concerns persist about whether these are sincere or cosmetic.

These halting reforms address staffing policies, “operational capabilities”, and technology-enabled information sharing (the lack of which arguably delayed the Ebola emergency declaration). WHO’s new Africa regional director Matshidiso Moeti insists that employee competence testing and job performance audits will be introduced, and regional reform “fast-tracked”.

Initiatives to strengthen preparedness assessments and boost contingency reserves are under additional consideration. However, these recommendations are stale relics from previous reform cycles. They were incompletely adopted then, and it is uncertain whether this time it will be different.

Despite this theatrical tinkering at the operational margins, outbreak-containment strategies still lack the much-needed “command and control” mechanism. At the early stages of epidemics, this power is essential to quickly mobilise personnel and resources, but there is currently no such global system. Given this vacuum, WHO should embrace its role as global first-responder.

However, WHO director-general Margaret Chan declined to acknowledge first-response as a WHO obligation, arguing instead that WHO is largely a “technical agency”. In a later interview, Dr Chan backtracked by saying that outbreak response is “in our (WHO’s) Constitution”.

Regardless, her initial view that countries have first-responder responsibility appears to be institutionalised in WHO systems. This weakness can be remediated on three fronts: centralised first-response capabilities, enforceable preparedness standards, and coordinated information systems.

First, response systems need further centralisation. Pandemics such as Ebola are global problems – a first-response system reliant on the efforts of individual countries exacerbates the threat of rapid contagion. Lacking confidence in WHO but aiming for coordination, some countries have pursued multilateral agreements for public health management. However, this fails to address the global nature of pandemics, instead favouring a retreat-and-fortify strategy that is politically expedient but fails to sustainably address the underlying problem. Centralisation should be global, not regional.

Absent central coordination, a poor response in one country can nullify diligent efforts in another. For example, Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf recently admitted to errors in handling the Ebola outbreak, specifically the deployment of military forces for quarantining. She later admitted that this response was unproductive and created unnecessary tension. Such cases raise concerns about varying levels of preparedness across countries.

Like other externalities, pandemics ignore political boundaries. In a modern world of international travel, their containment is dependent on worldwide cooperation and adherence to protocol.

Second, response systems must be complemented by long- term preparedness in resources, facilities and expertise. The latest crisis has exposed gaps in preparedness among high-risk countries. Not all reactive measures can be immediately coordinated from the centre, but proactive measures can be adopted in advance. This involves training responders in universal protocols and monitoring capabilities before outbreaks occur. WHO, therefore, becomes a response enabler, coordinating efforts and enforcing baseline standards across affected regions.

A similar approach has been taken to address another global threat: terrorism. The International Civil Aviation Organisation establishes international standards in flight security and helps the national authorities improve compliance. The global standards programme for outbreak response, coordinated through WHO’s Global Outbreak and Response Network, evidently needs a critical revisitation. Measures should go deeper in supporting systemic reform in individual countries’ capacities.

Finally, surveillance is a critical component of any outbreak response, underscoring the necessity not only of monitoring systems (which many countries already have) but also of information sharing and analysis. However, many countries lack the sophisticated analytical capacity to fully understand the data they gather. Analysis should, therefore, be centrally coordinated and informed by the work of international experts at the forefront of research and practice. Even a partial lapse in the quality and interpretation of outbreak information can countervail good monitoring elsewhere.

According to Associate Professor Phua Kai Hong of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, effective global pandemic response requires “the translation of science into operating systems through much stronger organisational structures to integrate both top-down and bottom-up levels”. Impolitic and infeasible though it may be to further empower multinational governance bodies, there are few alternatives. Nations and political leaders must suspend self-interest and cede some degree of strategic and operational control to a global response authority.

Despite some calls for a parallel agency, WHO is the only body with the resources, power and organisational apparatus to – after reforms – implement such a vision. Professor Tikki Pang of the LKY School argues that centralised coordination would benefit from WHO influence over the selection of regional directors, who are currently elected by regional member states.

Achieving the vision proposed here – response centralisation, preparedness standards and analytical capacity – will require strong leadership at the top of WHO and political will from regional directors and member states. According to Prof Phua, “WHO should forge a new mandate to mobilise more centralised funds and resources to strengthen and integrate the weakest links in its systems. It must go beyond its current passive role (and) towards building real capacity at the country level.”

The creation of a global response system, despite its seemingly authoritarian approach, is a fundamentally collaborative effort and nations must rally around a shared sense of responsibility for human life. However, transformative change may not be seriously considered until pandemics reach wealthy nations in significant numbers. At that point, it may be too late.

The first writer is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. The second is a doctoral candidate at the LKY School.

Source: http://bit.ly/1FrD82h