Asit K. Biswas and Kris Hartley

SANCHAR EXPRESS | January 23, 2015

China’s anti-corruption net appears to be catching tigers as well as flies. In December, a high-ranking party official was indicted on corruption charges. Ji Jianye had a turbulent tenure as mayor of Nanjing, and saw his career-long ascension through the Communist Party ranks stall abruptly on accusations of bribery. In the same week, a Chinese court sentenced a prominent businesswoman for bribery related to lucrative kickbacks from contract work. She was linked to China’s former railroads minister, himself convicted of bribery and abuse of power in 2013.

China’s crackdown on corruption is well publicized. President Xi Xinping has declared a commitment to indiscriminately root out all forms of corruption, from high level officials to minor bureaucrats. Nevertheless, despite some high-profile convictions and headline-grabbing investigations, China is failing to convince some Western analysts that it is truly committed. Transparency International’s 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index illustrates that the early stage of China’s war on corruption is not registering well in certain metrics.

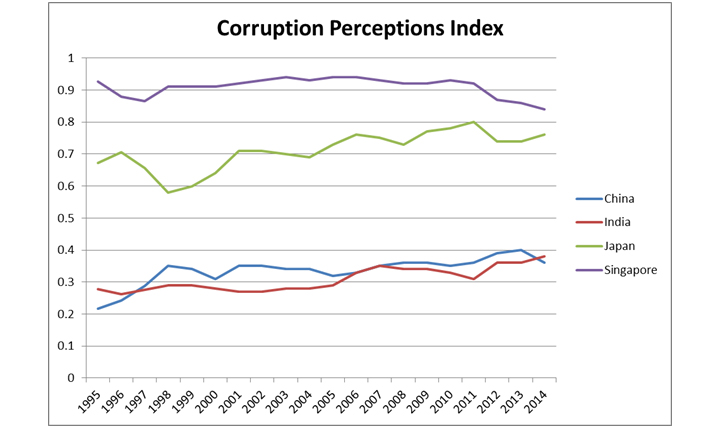

Through the late 1990s, China consistently improved its rank in the index (see chart). For the first decade of the 2000s, it held relatively stable and saw further improvement in the past several years. This upward trend, combined with the Chinese government’s stated resolve to tackle corruption, makes the latest index score more confounding.

Furthermore, after consistently outperforming India in the index since 1996, China has fallen behind its regional neighbor. China also experienced the greatest decline in index value among all countries besides Turkey. This produced a 20-place fall in the global rankings, where China is now in the company of Algeria and Suriname and behind the likes of Zambia, Liberia, and Panama. Regional peers have experienced similar volatility. Japan has progressed and regressed at regular cycles, although the country’s overall trend in the past 20 years is positive. Even Singapore, consistently among the world’s least corrupt, has slipped in recent years.

By contrast, the region’s second great power, India, has seen modest improvement in the 2014 index. Narendra Modi’s election victory is seen by some as indication of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty’s decline, and arguably signifies a growing optimism in new leadership. Anti-corruption demonstrations erupted across the country in 2011 and 2012, partly in response to the perceived weakness of the Jan Lokpal anti-corruption bill. Corruption has been a visible issue in recent years, and India’s performance in the index has improved modestly over that time. Its score had been low but steadily if slowly increasing since the 1990s, so the recent surge may be due in part to higher expectations related to these and other events.

As in China, prosecution of corruption cases in India has increased. In a recent interview with The Hindu, a Transparency International representative argued that India’s improved institutional conditions have supported more robust anti-corruption efforts, including the prosecution of high-level officials and bureaucrats. Improved information access and passage of anti-graft legislation were also seen as critical to these efforts.

Nevertheless, India’s improvement in the index is modest and corruption continues to plague upper levels of government, as do weak law enforcement and lack of whistle blower protection. Critics and activists have argued that new legislation has not gone far enough. Despite India’s improvement and small margin over China in the 2014 rankings—in addition to its reputation for having a relatively outspoken civil society and an active and largely uncensored media—the country continues to languish on certain anti-corruption metrics.

What accounts for the discrepancy between improved anti-corruption efforts and low performance in certain corruption indices? China has made a concerted effort but now lags India and is losing earlier gains. India has also taken steps to curb corruption, with only marginal results in the indices. Are recent accusations by Chinese officials of pro-Western bias in global corruption ratings warranted?

The issue behind this seeming disconnect is not how corruption is defined, but how it is detected, measured, and prosecuted. Notions of corruption are fairly universal, even between the East and West. Personal gain (typically financial) resulting from abuse of power, circumvention of procedure, undue political influence, and non-disclosure of assets can all be defined as corrupt practices. Nevertheless, the procedures through which corruption cases are prosecuted emerge from differences in governance cultures.

From the Western perspective, corruption in its systemic nature requires not only legal intervention but also institutional restructuring. The latter includes certain operating conditions within government that make corruption more difficult to conduct, such as an independent judicial system and institutional capacity to monitor corrupt practices. These metrics also include openness, particularly for related investigations. In the Western model, these are fundamental—if peripheral—qualities of any effort to root out corruption, and represent a preventative approach.

In China, the focus is on results. This approach holds prosecutions as the ultimate goal. On this ground, China has made progress. However, the systemic conditions that gave rise to such corruption may warrant further contemplation, and do not currently appear to be targets of reform. Instead, the approach assumes that prosecuting corrupt officials is enough to solve the problem, with ethical officials presumably remaining honest despite opportunities within the system to stray ethically. This not only places potentially undue faith in the morality of individual officials, but allows the government to argue that corruption is a personal failing rather than an institutional one.

Given this strategy, in corruption cases it is the official who is on trial, not the system. From this perspective, China’s corruption efforts make better sense. The approach grabs headlines, but it also preserves public faith in the current governance apparatus. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether political concerns dictate whom anti-corruption efforts target, and this is one of several concerns raised by external analysts.

The Western notion of corruption is fundamentally rooted in the tenets of democracy, including freedom of speech and media, government accountability, and protection for whistle blowers. Where these tenets are subordinated to systemic stability, such as in a Communist state, anti-corruption efforts are narrower in scope, often appearing arbitrary and inadequate to Westerners.

Transparency, another critical dimension of democracy, is difficult to measure absolutely. As such, surveys must be used to understand the degree to which respondents believe corruption is occurring, including opinions from business people and analysts at global financial institutions and international organizations. These “experts” are seen to be more reliable than the general public, which may be influenced by media. Nevertheless, when anti-corruption efforts are perceived to be shrouded in secrecy external analysts are likely to raise questions, for no reason other than the guarantees of adamant officials are insufficient grounds for certainty. This is the case for both India and China.

As the world has become increasingly interdependent, the governance ideals of Western countries (where corruption research most often takes place) are being used to judge emerging superpowers, fairly or otherwise. The question is whether Western observers – analysis, governments, and anti-corruption watchdog organizations – are willing to accept the credibility of claims from India and China about the robustness of anti-corruption efforts, or whether observers will continue to use limited information and speculation to make feebly substantiated accusations, particularly about weak political will and failure to observe specific sets of rules for transparency and judicial fairness.

These are difficult times for entrenched political parties. From the Arab Spring to the Hong Kong protests, a younger and more politically active generation is finding ways to steer global attention towards perceived systemic ills. The dividing line in the current corruption debate is universal access to information; the West sees it as paramount (if imperfectly practiced by many Western countries), while China sees it as an overbearing nuisance and ideological battering ram. Perhaps the next stage in the global debate is for China, India, and others to develop their own anti-corruption indices, presenting new metrics to the global marketplace of ideas and exposing the analytical shortcomings of Western analysis, if existent. Let the tiger show the eagle how to catch a fly.

Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, and co-founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management, Mexico. Kris Hartley is a doctoral candidate at the Lee Kuan Yew School of the National University of Singapore.