Cecilia Tortajada

SHANGHAI DAILY | August 4, 2014

Population growth, urbanization and higher consumer spending in China are major drivers of growth in the agro-food products industry, both domestically and abroad.

As China strives to satisfy demands at home, the figures can be striking — imports of oilseeds, for example, are expected by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization to rise by 40 percent over the next 10 years, accounting for 59 percent of global trade.

The country has also made substantial agricultural investments around the world, including in farmland, water and farming infrastructure, prompting concern about China’s role in the global scramble for resources.

Acquisition and management of agricultural land by foreign governments and private companies is raising fears about the potential impacts on food security, loss of sovereign control, appropriation and exploitation of natural resources and weakening of local livelihoods.

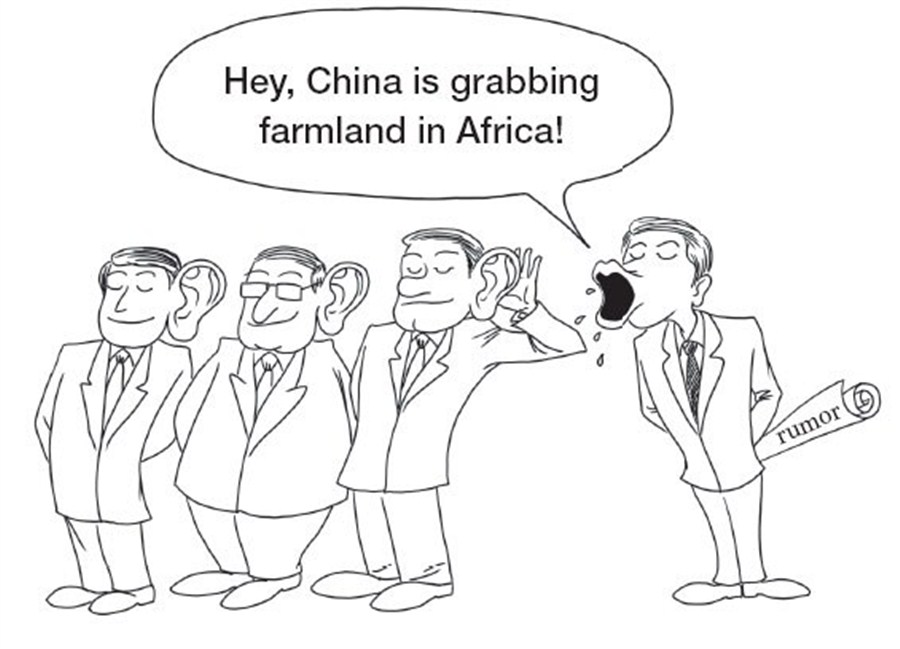

Media reports and even academic papers claim that farmland acquisition, or “land grabbing,” is occurring at an alarming rate.

China has been criticized for buying up and degrading farmland and natural resources in many countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, central Europe and Latin America, as well as exporting entire food productions through non-market means. This, say commentators, is compromising food security and driving poverty in host countries.

Wildly erroneous

However, much of the information in circulation about global land purchases is false, as research I conducted at the request of UNDP for the formulation of the Post-2015 Millennium Development categorically shows (http://www.post2015hlp.org/the-report/).

Many of the claims disseminated and repeated ad nauseum, are based on non-verified and unreliable media reports and on secondary and tertiary sources. When facts are carefully checked, assertions have proved wildly erroneous.

For example, the World Bank evaluated data from registries in 14 countries and found that some 56 million hectares of large-scale farmland deals were announced but never implemented between 2008 and 2009, and two-thirds of these were in sub-Saharan Africa. The data also show that farming had started in only about 21 percent of the agreements reached due to a range of risks related to host institutions, poor infrastructure, technology and price changes.

Land Matrix, the group that initially published the much-quoted figure of 83.2 million hectares of large scale land acquisitions globally, revised its estimate dramatically downward in June 2013 to 32.6 million hectares.

When it comes to China specifically, claims that the country is at the center of large-scale farmland acquisitions in developing countries are also on shaky ground. Experts working in the field have repeatedly said that, while China is investing heavily in many resource sectors, it is not hugely active in farmland acquisitions.

For example, international media have reported massive Chinese agricultural investments and interests in several countries in Africa, including US$800 million being invested in large-scale farming in Mozambique in the Zambezi Valley, with 20,000 Chinese workers sustaining these projects.

However, field research indicates that this is not the case.

Instead, many of the Chinese-operated farms in various African countries do not produce for large-scale export to China but for the local market.

In the case of Mozambique, field work did not find any proof of the above large investment and thousands of Chinese workers, but a Chinese training center operating on 30 hectares of land for hybrid rice farming. This is supported by studies by the Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative (SIANI).

The reports give a sense that Sino-African cooperation in agriculture that goes back to early 1960s is mostly in the form of foreign development cooperation projects and not agricultural land investments, as claimed by many.

Chinese aid projects

During the last more than 60 years, over 40 African countries have hosted Chinese agricultural aid projects and more than 90 farms have been developed through Chinese aid.

As of 2009, China had carried out about 200 agricultural projects, and another 20 in the fishing industry.

According to SIANI’s studies, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) has reported that there are over 1,100 Chinese agricultural experts in Africa, maintaining at least 11 agricultural research stations.

However, contrary to what is claimed, Chinese “land grabs” are not happening in Africa on the scale suggested.

These findings are also supported by research by the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Now that China has become a major global economic power and needs external resources to help its growth engine keep humming, “China bashing” over farmland acquisition has found a receptive audience in many parts of the world.

By the time the World Bank study was released and Land Matrix revised its numbers, the wrong figures had been quoted and re-quoted so extensively that they had been accepted by many scholars and media as truth.

This has unfortunately created an environment of misinformation and mistrust towards foreign farmland investment, mostly by Chinese groups.

Land grabs and their potential implications for food security at local, regional and global levels, as well as economic development and poverty alleviation in the countries concerned, are important issues and need to be studied carefully. This is still not happening.

There is good evidence that emerging economic powers like China and India are setting their own agendas in terms of access to natural resources beyond their own borders to ensure their continued economic growth in the future.

Nevertheless, lack of reliable data, poor research and extensive use of unreliable information have contributed to the current confusion and misinformation surrounding land grabs and their implications for food security, economic development and poverty alleviation.

In the age of ready information, availability does not guarantee accuracy. Land grabs and food security are clear examples. Accusations and assumptions, mostly against and about China, are shaping global public opinion, even though they are often based on flimsy and erroneous data.

More worrying, analyses are still not addressing fundamental issues such as what could be the most appropriate food security-related policies nationally, regionally and globally. Poor scholarship and extensive dissemination of untruths, by negatively shaping global public opinion, can only hamper truly effective initiatives to foster the development of impoverished regions.

Dr. Cecilia Tortajada is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. She authored the case study “Corporate Land Grabs: Policy Implications on Water Management in the South” for the Post-2015 UN MDG Development Agenda.

Source: http://bit.ly/W5Xlqt