Asit K. Biswas

TODAY | October 28, 2013

When I was a child, I admired James Bond very much because, whenever he was in enemy territory facing imminent danger, he intuitively knew which switches to press to get the desired results.

When we consider smart and resilient cities, I have no idea which switches to press to get the desired outcomes. Sadly, no one else really knows either. In fact, we do not even know if the right switches are on the switchboard for us to press.

What I am convinced of, however, is that the current near-total focus on technology as that switch is not right. Technology could be one of the factors that may help us to make our future cities smarter and more resilient, but it is highly unlikely to be the most important factor.

The world is now facing an immense challenge as tens of millions of people leave the rural areas each year in Africa, Asia and Latin America to seek a higher standard of living in cities.

While the cities of the developed world had many decades — sometimes a century — to cope with the rural exodus, the rate and extent of urbanisation in the developing world is unprecedented in human history.

Thus, the scale of city building and improvement needed in the Third World within a very few decades is going to be extraordinarily complex and challenging, especially as we still do not know exactly why some cities become vibrant and very liveable but others do not.

TECHNICAL BUT SOULLESS

City planning has always been difficult and controversial. In the 1940s, the Swiss engineer and art historian Sigfried Giedion warned that the instincts of the ruling class would restructure a city with the help of the technical elite, which could make it soulless.

In 1937, the distinguished American urban planner Lewis Mumford warned that housing and city planners “had no clear notion of the social functions of the city”. His view was: “The city fosters art and is art; the city creates the theatre and is the theatre”. It is in the city that “man’s most purposive activities are focused, and work out, through conflicting and cooperating personalities, events, groups, into more significant culminations.”

I recall how, in the early 1970s, impressed by what I had read about Brazil’s new capital city, planned by Oscar Niemeyer, I decided to visit Brasilia. I was impressed by the architectural beauty of the towers and church he had designed.

However, I was disappointed by its over-planning, overwhelming focus on cars for transport and unfriendly attitude to people.

It was barren. The city was too artificial and did not have a “soul”. I was so disappointed with Brasilia on the very first day that I decided to fly to Salvador, where things may be chaotic, but the city had soul!

Some 40 years later, Brasilia has started to develop a soul and character. Perhaps in another 50 years or so, it could become a great and liveable city.

‘ULTIMATE’ CLEAN CITIES

The current discussions about smart and resilient cities are invariably reduced to the use of more technology, more gizmos and significantly more information processing. Good engineering, which was the focus of the past urban planners, is now being replaced with advanced technology and focus on information processing.

Let us consider two cities which now receive the lion’s share of attention from the modern city planners: Masdar in the Emirates and Songdo in South Korea.

Masdar is being designed by Foster + Partners, whose main partner is Norman Foster, an eminent architect. It is supposed to be the world’s first zero-carbon city where, unlike Brasilia, it will have no cars. Instead, below the city, there will be a fleet of driverless cars which would transport people through dimly lit tunnels. The city is being built over a 9m-high base so it can take advantage of wind, requiring less energy for cooling.

Construction of this 6 sq km city started in 2008 and was expected to be completed by 2016 (now pushed back to around 2025) at a cost of US$22 billion (S$27 billion).

It is expected to house up to 50,000 people and will have some 1,500 businesses focusing primarily on environmentally-friendly products. Some 60,000 workers are expected to commute to the city daily.

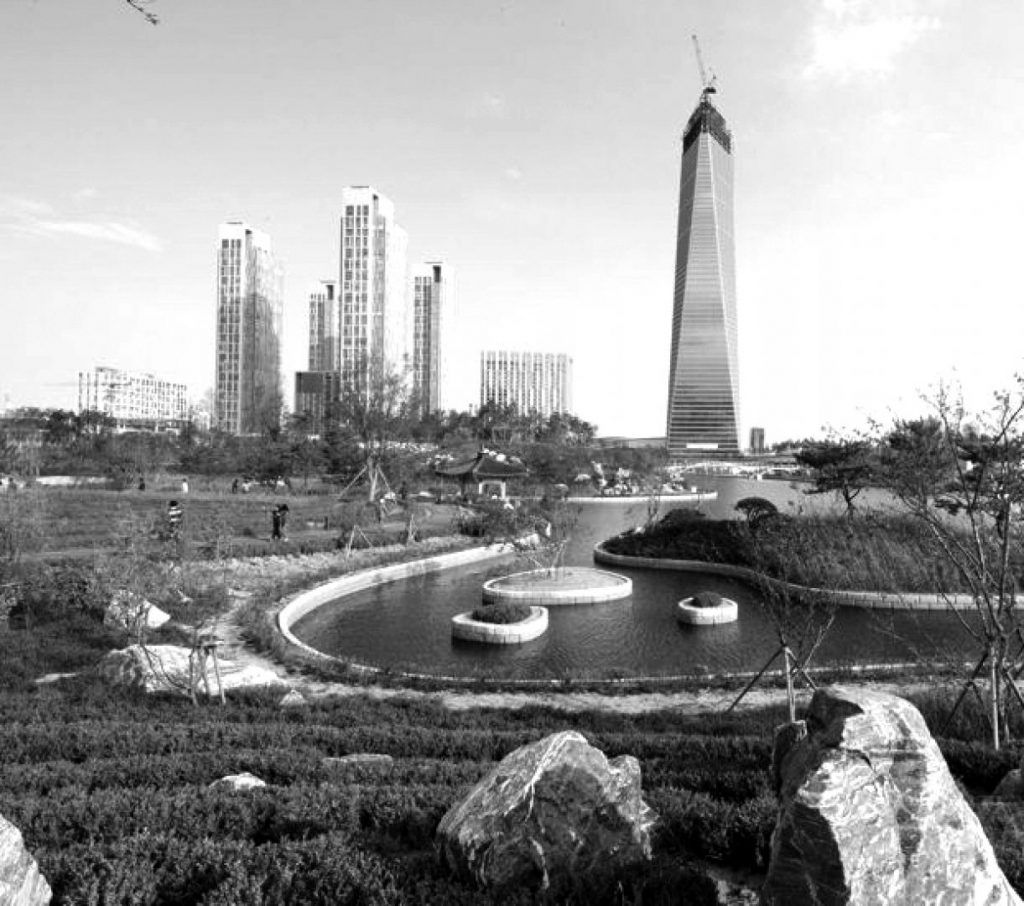

Another smart city that is being built from scratch is Songdo in South Korea. It is being built by a private-sector American-Korean consortium, on 607ha of reclaimed land at a cost of US$35 billion.

When completed in 2017, it is expected to be home to 65,000 people, while another 300,000 will commute to work in the city.

It is also expected to be the ultimate clean and efficient city, with normal city functions such as utilities, security, delivery and parking controlled by a central “brain”.

SOME MESSINESS, PLEASE

Are these smart cities the harbinger of the future? These meticulously over-planned and over-zoned cities may be today’s smart cities — but they might well become tomorrow’s urban deserts.

The inhabitants of such high-tech, information-rich cities may have their choices pre-determined and limited, such as where to shop or where to get a dentist most efficiently, but such cities are unlikely to help residents communicate and interact with one another so a community spirit can be created.

Based on sociological research over the past decades, conducted in cities such as Mumbai and Shanghai, it appears that what urbanities value most are basic services, including safety. However, once these services are available, they prefer quality of life over efficiency.

Cities are complex organisms and they thrive when they are messy and convoluted, which allows people to interact with one another and share their neighbours’ joys and sorrows.

The challenge that is facing the urban planners of tomorrow is how to transform each gali, soi or lorong into a village with a positive sense of neighbourhood.

More than 10 years ago, I attended a conference in Delhi, Does Delhi Have A Soul?. At the end, the participants unanimously concluded that Kolkata, messy though it is, had a soul, but Delhi does not.

All of us want to live in cities where all the basic services are available and the streets are safe, but which still have charm, are open to changes and uncertainties and emanate a good sense of neighbourhood.

THE CANCER OF EXCLUSIVITY

In a sense, cities like Masdar or Songdo are not new. The concept of exclusive developments for the rich and privileged in gated communities has been spreading extensively all over the world for several decades like a cancer.

Mr Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architectural critic of The New York Times, wrote about Masdar: “Its utopian purity and isolation from the life of the real city next door are grounded in the belief — accepted by most people today, it seems — that the only way to create a truly harmonious community, green or otherwise, is to cut it off from the world at large.”

Cities are not machines which can always be run efficiently. Technology can help, but it cannot be the master. It is possible to design striking architectural structures and also massive, efficient, tech-savvy and carbon-neutral buildings — but what we still do not understand very well is how these structures and people who live and work in them can fit together to create a vibrant and liveable city.

Great cities evolve over time and their greatness also ebbs and flows with time. Perhaps, like Brasilia, over the next 100 years, smart cities like Masdar and Songdo may evolve into liveable ones. Even so, urban planners should be aware of the pitfalls of adopting these smart cities as models simply because they are seduced by their technology applications and efficiency.

As Walt Whitman said: “The great city is that which has the greatest man or woman. If it be a few rugged huts, it is still the greatest city in the world.”

Asit K Biswas is the Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore, and founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management, Mexico.

Source: http://bit.ly/1e8KEnQ