Asit K Biswas and Julian Kirchherr

UBM’s FUTURE CITIES | October 13, 2012

Water demand exceeds supply by 300 billion cubic meters. In 20 years, demand will overshoot supply by about 40 percent. This gap is solvable if we embrace used- and waste-water.

A central weakness of cities today in managing water is their failure to collect and treat used water to enable its subsequent reuse. Water, unlike oil or coal, is a renewable resource. It can be used, treated, and used again, on a continuous cycle. It is estimated that every drop of the Colorado River is used seven times. With better management, it can be reused even more.

The Third World Centre for Water Management has estimated that only about 10 percent of wastewater from urban centers of Latin America is collected, properly treated, and then discharged in the environment. The situation is likely to be similar in developing Asian countries and probably worse in Africa. This doesn’t have to be so.

Take the case of Singapore. It collects and treats all of its wastewater. In fact, its wastewater treatment plants produce a higher quality of water than its taps. Indeed, Singapore’s so-called “NEWater” now meets more than 30 percent of the country’s water needs and is expected to meet 50 percent by 2050. Such extensive reuse helps Singapore to reduce its reliance on water imports from Malaysia (currently over 50 percent), improves its water security, and lessens the demand for fresh water.

But there are at least two impediments to implementing such extensive water systems reuse in cities. One is consumer attitude.

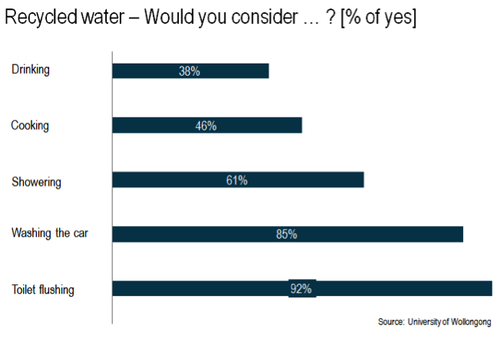

Reusing water means embracing the “toilet to tap” paradigm, turning wastewater into drinking water, and some countries like Australia or the United States have experienced consumer resistance. The general public still believes recycled water poses health risks. A 2010 survey carried out in Australia found that only 36 percent of respondents would consider drinking reclaimed water. Fifteen percent would not even wash their cars with it!

The second impediment is the economic cost of using properly treated wastewater. Even though the costs are coming down, some cities may not be able to afford it nor have the technological and management know-how to accomplish it.

Singapore and Tokyo have reduced their water losses from the system to around 5 percent. In contrast, losses from cities of the developing world often range from 40 percent to 70 percent. The world’s largest privatized water utility, Thames Water of England, loses 26 percent. The world’s urban water problems can never be resolved with such poor governance practices.

In order to solve the world’s urban water problems, water has to be properly priced. Utilities, whether public or private, must have a viable and sustainable financial model. The world does not have enough water if it is provided for free or at a highly subsidized rate. The consumers must pay for it, and any subsidy has to be very specifically targeted toward the poor.

Singapore has proven that consumer resistance to use treated water and higher prices can be circumvented by education, as well as proper long-term planning. Water recovery technologies are likely to improve over time and will become increasingly more cost-effective. Meanwhile, higher prices should spur consumers to reduce their total water consumption.

The world’s urban water problems are solvable. What’s needed is political will, good water governance, and consumers who are willing to pay a reasonable price for a supply of good quality water and much improved service delivery.

Asit K. Biswas, Founder of Third World Centre for Water Management; Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School for Public Policy in Singapore and Indian Institute of Technology, Bhubaneswar, India; and Julian Kirchherr, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Article published in UBMs Future Cities, October 13, 2012.