Asit K. Biswas and Leong Ching

THE STRAITS TIMES | July 4, 2011

WITH so many water weeks across the globe, what can the Singapore International Water Week starting today offer?

Before Singapore, there was Stockholm. After, there is Berlin, Milwaukee, Tel Aviv, Amsterdam and Toronto. Is there a need for so many water weeks in different cities of the world?

The short answer is yes, provided they can find their respective niches and make positive contributions.

Stockholm, the leading organiser of the event now into its 21st year, tends to be somewhat academic with a focus on international institutions. Singapore has established itself as a business-oriented “one-stop shopping centre” for water technologies, while Berlin is making a determined attempt to be multisectoral in terms of water for all purposes, including food, energy and environment.

Stockholm claims to provide cutting-edge knowledge while Singapore aims to be a thought leader. But there are subtle differences. Stockholm deals in all aspects of water, whereas Singapore focuses almost exclusively on urban water and wastewater management.

The Stockholm Water Prize is given to eminent people working on all aspects of water issues and is generally accepted as the “Nobel Prize” in the area of water. In contrast, the Lee Kuan Yew Water Prize has a much narrower focus: Over the past four years, it has been awarded for research in urban wastewater management three out of four times.

There is room for both broad and focused approaches In the new millennium, there is a new thirst for water, pushed by ever increasing population growth, urbanisation, industrial developments, technological advances, and the uncertainties of climate change.

Unfortunately, water governance in nearly all countries of the world in the past has been poor and looks likely to remain so. Yet, unless governance improves significantly, it is unlikely that the water problems of the world can be resolved.

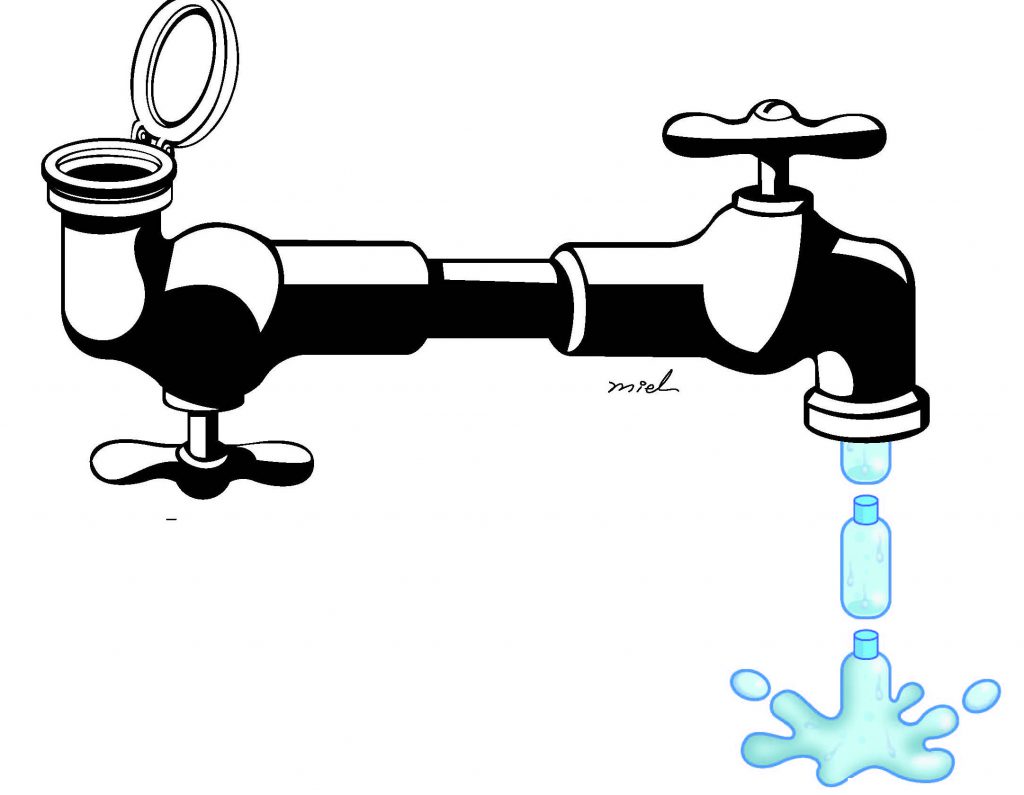

Population growth, higher urbanisation and higher standards are important drivers for increasingly higher demand for water. Estimates are varied but all sound a clarion call for the need to deal with burgeoning populations in cities. In 2008, for the first time in human history, more people lived in cities than in rural areas. This means more attention needs to be paid to basic infrastructure and such unglamorous things as pipes and plumbing, which people take for granted and seldom deliver votes for politicians.

Before 2000, the oft-cited figure is that one billion people do not have access to safe drinking water and 2.4 billion lack access to good sanitation. A decade on, many people realise such figures are meaningless since they have no link to the quality of water.

The Third World Centre for Water Management estimates that at least 1.8 billion people do not have access to clean water that can be drunk without any adverse health effects. The centre also estimates that only about 10 per cent of people in Latin America have access to good wastewater treatment, with a similar situation in Asia’s developing countries and somewhat worse in Africa. Consequently, many rivers in cities have become urban sewers.

This is where international water weeks can make a difference.

These events are watering holes for international organisations and individuals to meet, share ideas and forge partnerships.

Stockholm, with its strong attraction for international organisations, is a good channel for matching communities with international donors and funds.

Singapore International Water Week, with its focus on dealmaking and practical outcomes, provides a different value: business deals.

Singapore has a well-deserved reputation for good governance, including an efficient regulatory environment for both financial and business law. It also has an international outlook, reaching out to investors in the West and the South, and opportunities wherever they may lie.

Last year’s Singapore water week saw a record increase in the number of trade attendees to over 14,000 from 112 countries and regions. The total value of announcements of projects awarded, tenders, investments into Singapore, and research and development memorandums of understanding exceeded $2.8 billion, up by 27 per cent from 2009’s $2.2 billion.

We have pointed out the niches of different water weeks in different countries. There remains one important niche that is unfilled – looking to the future.

Water problems in 2025 will be vastly different from today’s – partly because of crises in different sectors which will have a profound impact on water; partly because of uncertainties brought about by globalisation, free trade, technological and climate change, and migration.

All this will lead to the eventual dissolution of existing water paradigms. The water week that will emerge as the top in 2025 will be the one that focuses on the rapidly changing world, and continuously adapts itself to meet these changes. The world needs “business unusual” solutions for water problems that we cannot foresee today. The city which can meet this challenge successfully will be the global winner.

The first writer is a Stockholm Water Prize Laureate (2006), a distinguished visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) School of Public Policy and president of the Third World Centre for Water in Mexico. The second writer is a PhD candidate at the LKY school.

Article published in The Straits Times, July 4, 2011