Asit K. Biswas

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST | July 20, 2015

According to the World Bank, Hong Kong’s per capita gross domestic product is US$40,169. This is higher than Japan’s, Italy’s or Spain’s, and only 5 per cent less than that of France. However, even for such a developed region, its water management practices are light years behind a place like Costa Rica, whose per capita GDP is about one-quarter that of Hong Kong.

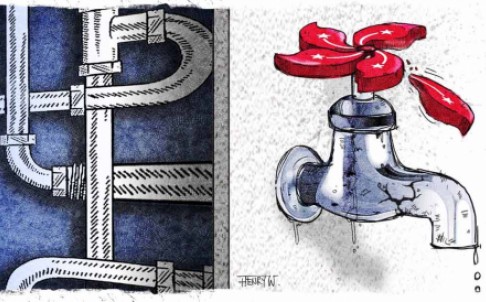

During the past fortnight, Hong Kong’s water supply system received a double whammy – the first punch being excessive lead content found in drinking water at a growing number of housing estates, and then legionella bacteria found in one location.

Let’s assess both short- and long-term implications of these developments and offer a possible road map to move Hong Kong’s water management system from the Third World to the First World.

Normally legionella outbreaks have been traced to humidifiers of air conditioning systems, hot and cold water supply systems and industrial heating and cooling processes. Transmission is primarily by inhalation of aerosols containing the bacteria. We have to wait until the investigations are completed, but it is unlikely that the city’s water system is directly responsible for this outbreak.

While legionella outbreak is an immediate health threat, higher concentration of lead is a different story. It is difficult to decide what the highest permissible level of lead in drinking water should be for health reasons. The lead level in the United States is 50 per cent higher than in Europe or Hong Kong. The European drinking water directive of 1980 allowed five times as much lead as it does now. In 1993, the World Health Organisation amended its guideline value to a maximum of 10 micrograms per litre, and the European Union adopted that standard in December 2013.

What needs to be investigated in Hong Kong is how long this high level of lead has been in the water, how it got into the system, and why the Water Supplies Department’s surveillance system failed to identify the problem promptly. Also, are there other pollutants in the water system?

If this high level of lead has been in the system for one to three weeks, it should not be a serious problem. However, if lead has been present for months or years and was undetected, and if there are other hazardous contaminants in water, their potential synergistic adverse health effects need to be carefully investigated.

Over the long term, the major impact will be that more and more people will lose confidence in the quality of water they receive. Already, an overwhelming majority of Hong Kong households boil water and/or use sophisticated point-of-use treatment systems. It is impossible to find such data in the website of the Water Supplies Department. Based on anecdotal evidence, our guess is that more than 80 per cent of the households now do not trust the city water enough to drink straight from the tap. Lead and legionella are likely to further accelerate the erosion of trust in the city’s drinking water quality.

In an earlier opinion piece, I noted Hong Kong’s water supply now is worse than in many Third World countries. If water management is to improve significantly to reach First World standards, the first action has to be for the department to accept that its policies over the last several decades have been dismal failures.

The fact is the average person in Hong Kong uses 220 litres of water every day; most water-efficient European cities use half that much. The figure of 130 litres often cited by the Hong Kong authorities ignores 90 litres of seawater that is used for hygiene purposes. Thus, comparing it with the European figure, which includes water used for hygiene purposes, would be like comparing apples with oranges.

In fact, if water management were reasonably efficient, there would have been no need for two systems in the first place – one for freshwater, the other for seawater.

In addition, the department failed to foresee the large-scale movement of industry to the mainland due to cost and other reasons, which meant its forecast of future water requirements were too high. Because of continuing poor policies, domestic water use in Hong Kong is twice what it should be. With efficient water management, water imports can be reduced dramatically.

If water management in Hong Kong is to be in the same league as the best in similar affluent cities, the department should look at all aspects of current and future water policies and propose a feasible strategy. This should include issues such as demand management; efficient use of water available; proper water pricing and targeted subsidies for the poor; extensive reuse and recycling of properly treated wastewater; behavioural changes by water consumers through education; prompt adoption of technological innovation; and institutional strengthening.

About three decades ago, it was fairly common to hear that if one wanted to learn something new and innovative, the place to visit was Hong Kong. During the past two decades, the “go to” place has been Singapore, and Hong Kong is not even on the radar. Yet, the city has the knowledge, technology and potential to transform itself to a pre-eminent position.

However, to achieve this, the policymakers will have to make some hard decisions, bureaucrats must accept that water management is in a mess, and instead of making excuses, they should try to be the best in the world. The public must demand a first-rate water service, and the media should hold the feet of policymakers and bureaucrats to the fire when they do not deliver. Hong Kong’s water supply system can be the envy of the world in about one decade.

Professor Asit K. Biswas is the distinguished visiting professor at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore, and co-founder of Third World Centre for Water Management, Mexico. He received the Stockholm Water Prize, equivalent to a Nobel Prize in the area of water, in 2006.

Source: http://bit.ly/1JeG1W4