Cecilia Tortajada and Asit K. Biswas

THE STRAITS TIMES | September 2, 2014

Emerging economic powers such as China and India have been negotiating for a greater share of voting powers in multilateral development banks including the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Asian Development Bank (ADB).

They want vote shares that would reflect their growing economic and political power.

China, for example, is now the world’s second-largest economy, but its voting power in the Bretton Woods institutions (IMF and World Bank) amounts to only 4 per cent, compared with 18 per cent for the United States.

The present situation is frustrating for these emerging economic powers – with less voting power, they have less influence within these institutions and less say about where the money from these organisations could go. Many developing countries are also fed up with the seemingly unfair conditions imposed on them by the Western powers.

After many years of negotiations, the US Congress rejected legislation that would reorganise the voting power of IMF member countries.

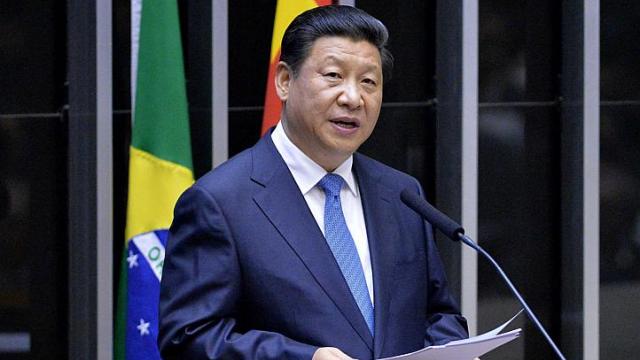

It was against this backdrop that Chinese President Xi Jinping announced plans in October last year to set up a new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), during an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) meeting in Bali, surprising his Indonesian hosts.

In his speech at the National Congress of Brazil on July 16 this year, Mr Xi further elaborated his views in terms of promoting the “establishment of a new type of more equal and balanced global development partnership”. He also discussed ways to strengthen coordination and cooperation within international and multilateral mechanisms “so as to win institutional power and rights of voice for developing countries”.

The framework and modus operandi of the proposed AIIB are still being worked out, but the need for such a bank is beyond doubt. According to ADB, countries in Asia need US$8 trillion (S$10 trillion) to cover their national infrastructure needs for the period 2010 to 2020. This works out to an average of US$800 billion a year. Currently, ADB lends only about 1.5 per cent of this amount annually.

Countries provide some funds from internal sources, but much of the development needs remain unfulfilled. Thus, any additional funding from the proposed bank would be welcomed by Asian developing countries.

From China’s standpoint, such a bank makes eminent sense. A major feature of its sharp economic progress has been its emphasis on infrastructure development. During the 20-year period spanning 1992 to 2011, it spent what amounted to nearly 8.5 per cent of its gross domestic product on infrastructure. Corresponding figures for other Asian countries are between 2 per cent and 4 per cent.

The AIIB would serve at least five objectives for China.

First, China could invest part of its US$3.9 trillion in foreign reservers on commercial terms. Second, the bank would aid the internationalisation of the yuan. Third, it would help secure contracts for Chinese firms and thus boost employment potential at home.

Fourth, China has funded numerous infrastructure projects around the world through the China Development Bank and the Export-Import (Exim) Bank of China. Some of these projects have fuelled local resentment. There might be less resentment if the funds were to come from a regional bank such as the proposed AIIB.

Finally, the new bank would boost China’s influence internationally and enhance its “soft” power.

Mr Xi’s proposal has ruffled some feathers, especially in Japan and the US, which are likely to lose some power and influence.

Japan is not convinced that there is a need for such a bank. Tokyo and Washington have worked together to maintain the power structure in the 67-member ADB, where the US holds 15.6 per cent of the votes and Japan 15.7 per cent. China holds only 6.5 per cent. Reports indicate that the US has put pressure on South Korea not to join the proposed bank.

Media reports indicate that 22 countries are ready to sign the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on the framework of the bank as founding members; the MOU is being prepared by the Chinese Finance Ministry. Reportedly, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has discussed India’s membership with New Delhi.

During a visit to China last month, Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean “expressed Singapore’s intent to accept China’s invitation” to become a founding member of the AIIB.

The Chinese proposal has also created turbulence at the World Bank and the Manila-based ADB. A senior official of ADB recently said that unless the new bank has the “highest standard of governance”,? ADB will have difficulty cooperating with it.

Unnoticed by the world, and certainly by the World Bank and ADB, China has already outflanked them very comprehensively in many areas.

Take investment in water infrastructure. No one really knows how many dams China is financially supporting abroad. International Rivers, an anti-dam organisation, claims that Chinese companies are involved in some 304 dams in 74 countries. Unquestionably, the figures are a gross overestimate. But even if China were involved in only 25 per cent of the dams claimed, that would still be more than four times the number of dams funded by the World Bank and all regional development banks combined.

The AIIB is expected to be capitalised at US$100 billion. ADB tripled its capital base only in 2009, from US$55 to US$165 billion. Thus, the AIIB would start life with what amounts to about two-thirds of the current, expanded capital base of ADB. Thus, the AIIB could become a competitor to ADB and the World Bank in terms of providing funds for bankable development projects.

The Chinese have considerable experience in planning and constructing infrastructure and in financing infrastructure projects outside China. As Chinese Finance Minister Lou Jiwei has noted, the China Development Bank’s commercial infrastructure loans now far exceed those of the World Bank and ADB combined. The Exim Bank of China is supporting projects in Africa, most Asean countries, Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America.

China and its banks have been accused of not following good governance standards and of ignoring environmental and social concerns when lending to developing countries. Projects within China have often suffered from similar shortcomings. However, China is learning fast, and trying to rectify these problems both at home and abroad, as reflected in many of the latest initiatives aimed at strengthening governance in its banking sector.

No one can foretell how effective the AIIB will be. A China-backed and massively financed new regional bank would shake things up in the current setup dominated by Bretton Woods institutions by injecting a healthy dose of competition.

Cecilia Tortajada is a Senior Research Fellow in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore. Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the same School. Both are co-founders of Third World Centre for Water Management.

Source: http://bit.ly/1KCEJDc